Posts Tagged ‘race’

Memorial Day Lesson from a Daughter of the Confederacy

On a run last week, Erin had noticed that Oakland Cemetery, which we’d never visited, had sprouted Confederate flags. We went back to look today, figuring we’d find another memorial to the mythical Southern Way of Life and the Lost Cause.

Instead, we found a 65-year-old white woman named Marquita talking to a younger black woman and a black man amid the headstones. The black woman, angry and crying, was struggling to find her father’s burial site. The man was there to put flowers on his daughter’s grave, now an overgrown patch of weeds, and to find another family member.

Marquita, who recently joined the Daughters of the Confederacy at her brothers’ behest, also has relatives buried at Oakland. Black and white buried together, something we haven’t seen in old, post–Civil War and segregation-era cemeteries around here.

We walked up to the group as Marquita explained to the woman why she couldn’t find her dad’s grave. The cemetery’s owner, Allen Simmons, had buried people every which way—casket atop casket, pointing this way and that, under walkways—with or without permits. Over the years, Simmons and his company, Oakland Estates & Grounds LLC, got hauled into Hampton court and dinged for misdemeanors like “improper upkeep of cemetery.” Found guilty more than a few times, Simmons was fined—$2,500, $1,000, $500—didn’t pay, and kept on disrespecting the dead.

In 2005, Simmons told a reporter from the Daily Press, the local paper, exactly where he stood: “I kind of agree with the city. They have something to complain about,’” he said. ‘But our plan is to abandon the cemetery because we have no funds.’” And abandon it he did; and then he died.

The Commonwealth of Virginia doesn’t want to take responsibility for Oakland, nor does the city of Hampton. There are, however, plots at Oakland that are picture perfect—headstones upright, grass manicured. Families with means take care of these, but only these.

So, like the city’s primarily African American cemeteries, this rare integrated burial ground would be totally consumed by nature if not for a band of volunteers.

Marquita Latta plants flags at upended headstones of black servicemen, Oakland Cemetery, Hampton, VA, May 24, 2014, BP cell phone photo

Marquita is a voluble woman, today wearing a cowboy hat glittered in blue with white stars to match the stripeless corner of Old Glory. I hope she won’t mind me calling her eccentric, because she is. She’s adopted Oakland, along with a group of people she calls family—Tim, a Son of the Confederacy, who was cutting the grass on his new riding mower; Sarah (I think that was her name), who was doing the same on the old one; and others. When Erin and I arrived, they had all been trying to help the crying woman find her dad’s grave. They stuck a thin metal probe into the earth, hoping to hit stone or anything hard; then they dug a small hole. Nothing.

Marquita peeled off from the group to show me something at the far end of the cemetery, a heap of six headstones—all of them official Veterans Affairs, government–issued ones. African American service members, she told me. She and her comrades had pulled them from the woods but didn’t have the equipment to set them upright. She’d called the VA, she told me, and the local black chapter of the American Legion. More nothing.

As I stood there, this Daughter of the Confederacy—as in an actual member of that national organization—added a few more American flags to the ones she’d planted before we arrived.

Erin overheard Tim talking to the man who came to visit his daughter and find his relative’s grave marker. They didn’t find it—so Tim, the Confederate Son (this according to Marquita), dug a small hole in a spot where the grave might be, just the right size for the African American man to fit a vase of flowers. Tim asked where the daughter was buried and then piloted his mower over to the plot and cleaned it up. The man (he left before I got his name) then planted his second tribute, a bouquet of white flowers.

As we pedaled away, Erin waved goodbye to Tim. He returned the gesture with the flag he was holding, the Confederate stars and bars.

(Where’s the) Rage against the Machine?

The University of Alabama’s student government may have flip-flopped its way into the 21st century. In mid-April, UA’s senate voted to adopt a resolution supporting the racial integration of the school’s nearly all-white fraternities and sororities after killing a similar measure just a few weeks earlier.

On its face, this is a historic move. To alumna Jessica Patrick, it may very well be “a step in the right direction” toward greater diversity. Patrick—Jessica Thomas while at UA and now a an attorney in Nashville—was the subject of Bama Girl, a documentary that chronicled her 2005 campaign to become UA’s first African American homecoming queen. (Along with other candidates of color, she lost.)

History, however, gives us ample reason for skepticism. Former governor George Wallace made his notorious stand in 1963 on the steps of the school’s auditorium for the “southern way of life,” known nowadays as “state-sanctioned racial discrimination,” and against the enrollment of Vivian Malone and James Hood. More recently, UA has made national news for eruptions of old-school Dixie racism in the social sphere. The Crimson White, the school newspaper, ran an exposé in 2013 of the systematic exclusion of African Americans from prominent and powerful white fraternities and sororities.)

The recent resolution is a symbolic statement by students, not a plan of action that commits anyone to do anything, including the school’s administration. But it is something, one might say. “It’s only a step forward, but it is a step forward, and it should be encouraged,” University of Alabama law professor Paul Horwitz said in an email.

The Root requested comment from the University President’s office about the measure but received only a general statement asserting the university’s commitment “to a welcoming and inclusive campus.” University President Judy Bonner did speak out against the segregation of and discrimination by white Greeks last year after the Crimson White’s 2013 investigation, which revealed that two high-achieving African American women had been rejected by 16 sororities. (The U.S. Justice Department found that situation so serious it assigned a U.S. Attorney to monitor the situation.)

Nathan James, a Crimson White columnist, sees the yes vote as a straight-up PR move. “It’s clear from the previous vote where our senators’ loyalties lie, and that hasn’t changed because media pressure forced them to backpedal,” he wrote in an email to The Root. The “pressure” James describes built up after national and international news media hammered student government’s March 2014 decision to kill the first “diversity resolution.”

Terence Lonam, a progressive activist on campus from the class of 2017, is similarly skeptical. “When the last SGA senate voted to kill the original integration resolution, which I think honestly represented the state of race relations in Greek life at Alabama, I was horrified but not shocked – the powers that control a large segment of my campus, namely the Machine, are stuck to traditions that have kept them in power with relative ease.”

The Machine? Yes, “the Machine,” a secret society with deep roots in the muck of Jim Crow whose members are chosen from 28 of the school’s white Greek societies. The Machine has fought the move to integrate the Greeks through the immense—and stealthy—political power it wields in student government. A chapter of Theta Nu Epsilon, an umbrella organization of historically white Greeks founded in 1870, the Machine has operated and schemed at UA for a century. No surprise that it’s kissing cousin to Yale’s Skull & Bones.

So how does the Machine run? “UA’s Greeks vote in a bloc,” explains James, “they always elect representatives from a specific set of Greek organizations; these representatives, once elected, fight to preserve a segregated Greek system; students who run against Machine-backed candidates are frequently the targets of harassment and death threats; and elections featuring Greek candidates are frequently affected by voter fraud.”

“Death threats” leaps off the page. So we asked James to substantiate that charge. He provided links to news stories, including one from CNN, in which students made credible claims of such threats and other forms of nefarious Machination. Some, like the CNN.com piece, are more than a decade old. Others are quite recent.

“The Machine shouldn’t be overestimated, but the simple fact of its continued secretive status should be recognized as an obstacle to everything else the University of Alabama, its students and administration, want to achieve,” said Horwitz.

He writes with some authority. His wife, Kelly, was defeated in a Tuscaloosa city—not UA campus—election for Board of Education by Cason Kirby, a 26-year-old recent UA law school grad and former SGA president, under dodgy circumstances. AL.com ’s reporter on the UA beat, Melissa Brown, and others reported on emails sent to voting-age students by Machine-connected Greeks, pledging free booze and limo rides to the polls. (Kirby, a former member of Kappa Sigma, a frat identified in the Crimson White investigation as Machine-connected, did not return a phone call from The Root.)

Horwitz notes that grassroots opposition to Machine politics cannot be ignored. “Some of the most important moments on campus this year—complaints and marches about continued segregation, resistance against adults who were involved, disgust with corrupt voting-bloc tactics that spilled off campus this year and into the local school board elections—came about because of undergraduates, mostly in the sororities, who were disturbed by what they saw and heard and willing to put themselves on the line to do something about it.”

So where does that leave us? With a student organization that has Alabama influence and national ties and clings tenaciously to inherited privilege and power. It may not be able intimidate and machinate with impunity as it did when it still had Jim Crow muscle, but it remains an influential and clandestine political bloc —members do not acknowledge the group’s existence—at a public university with a long history of racial discrimination.

The Machine’s power endures in large part because the UA’s leaders, the adults in the administration, have chosen to remain silent about the group for decades upon decades. Their silence equals tacit approval. That tacit approval amounts to active support for a secret clan of hyperempowered and historically privileged youth to discriminate.

“The Machine is not all-powerful or all-important,” Professor Horwitz wrote in a recent Crimson White op-ed. “But as long as it’s around, every other problem will be that much more intractable. It needs to become a public, accountable group. Or it must be killed, forcefully and publicly.”

God Sees All

Charles Byrd drove his front-end loader to the end of the gravel road. He cut the engine, hopped out of the cab, and nodded at me. “That’s Maggie Walker’s grave,” Mr. Byrd said. I had just photographed the curved headstone without noticing who it honored, Maggie Lena Walker: savings bank founder, newspaper publisher, civic leader, Jim Crow battler, daughter of an enslaved woman.

Under my feet.

Mr. Byrd, a contractor, said he was heading to the mausoleum that Mr. Harris, who was working in another part of Evergreen Cemetery, had told him about. He took a narrow, grass footpath that looked promising into the trees.

Mr. Byrd shouted for me in barely a minute.

As you approach from the side, the crypt looks more stately than spooky. The part of the building that isn’t obscured by leaves and branches appears solid. Tendrils of ivy creep down the walls from its roof. But as you swing around to the front, down a slight hill, you see tragedy head on—a huge, ragged hole has been punched through the cinderblock façade. I gather that the ugly gray bricks had been laid to cover an earlier desecration of the original door. The name carved into the stone at the top of the structure is “Braxton.”

We stared into the hole at the exposed coffins.

“Why would somebody do something like this,” Mr. Byrd said, not asking me, just saying.

I feel this whenever I document human ugliness: a surge of adrenalin and my news reporter’s predatory hunger mashed up with disgust and anger. Sadness, too.

Rust had destroyed the finish of the casket directly in front of us. The fixtures were busted. The lid had been wrenched off. The two caskets to the right had been dragged off their shelves as far as they would come. The floor was heaped with shattered headstones, trash, a woman’s wig. It seemed that the people who did this had plenty of time to destroy and despoil. We didn’t know how awful the story was—the dead had been pulled from their caskets—until afterward, when we Googled our way to video a by KIDA Productions. (Scroll down to “Evergreen Cemetery: History in Ruins.”)

Evergreen Cemetery is enormous. It’s part of a patchwork of African American graveyards that covers acres of Richmond’s east side, East End Cemetery among them. Hundreds, possibly thousands, of graves have been absorbed by the forest. They are invisible beneath the green and brown tangle. Volunteers from the Virginia Roots Cemetery Restoration Project, local colleges, professional landscapers, even the army’s Fort Lee do regular cleanup operations. A local chapter of black fraternity Omega Psi Phi minds the plot where Walker and John Mitchell, Jr., editor of the Richmond Planet, are buried. But nature is very aggressive here, hard to fight with limited resources; the cemetery’s owners made no provision for perpetual care, which led to its current state. And then there are the vandals. (Volunteer wrangler John Shuck tells us that “an issue” with the owners of Evergreen has ended cleanup efforts there. Volunteers are now working at East End. Here’s a link to their Work Calendar for folks who want to pitch in.)

In red marker, someone has written on the center coffin, “God Sees All”; and at the rim of the hole, “Smile. Your [sic] On Camera.” Perhaps a deterrent to further outrages. Perhaps not.

Postcards from the Great Dismal Swamp

Ever since I came across the Great Dismal Swamp in the Rand McNally road atlas, I’ve wanted to see the place for myself. I’ll confess that this whole region—in fact, pretty much all of Virginia—was indistinct in my mind. (And I’m someone who loves maps and geography, thanks to my proud shunpiker parents, who pored over the atlas before every car trip in search of the roughest, remotest roads they could find.) It only began to take shape on our third voyage south, when we turned Brian’s lost passport into an impromptu honeymoon down the Eastern Shore, over to Hampton, on to Petersburg, and up through the Shenandoah Valley. That’s when I started to study the map.

It’s also when I started to study American history, my knowledge of which was patchy at best. I’d never been all that interested in pilgrims and pioneers, Rough Riders and robber barons, Confederates and carpetbaggers. But as Brian and I delve deeper into the history of slavery, the Civil War, and the dark decades that followed, the southern landscape has begun to take on new meaning for both of us.

Somewhere in the piles of articles and books and pamphlets we’ve accumulated, I had read that enslaved people sought refuge in the Great Dismal Swamp on their long journey to precarious freedom in the north. The twisting, infinite waterways and thickets of underbrush provided cover from slave hunters and their snarling bloodhounds, but it was a forbidding shelter, infested with mosquitoes and other beasties, snakes, and bears. Even so, for many it was preferable to bondage, becoming more than just a stop on the Underground Railroad, a permanent hiding place and home.

Colonies of maroons established themselves in the swamp, perhaps as early as the late 17th century, according to J. Brent Morris’s recent New York Times post, raiding neighboring plantations, then retreating to the thorny, bug-ridden bog to elude any pursuers. The whole piece is fascinating, but this bit is worth quoting at length:

The considerable numbers of maroons who used the swamp as a base for these attacks, as well as those who settled in the innermost communities of the deep swamp, were constant thorns in the side of plantation society, both militarily and ideologically. Through trade, appropriation and their own ingenuity, maroons obtained or made weapons and developed remarkable skills as guerrilla fighters. Just as important, however, was their symbolic variance from the ideological foundations of American slavery: the notion that African-Americans could not survive without benevolent white supervision, that they did not truly desire their freedom and that they were pathetically inferior to the ‘master race” in every way. Rather, they challenged white authority and stood for centuries, unsubdued, as a powerful rebuke to the Slave Power.

It was this article, in fact, that spurred us to action on Sunday. (Oddly enough, a few days before, during a marathon session at the University of Chicago’s marvelous Special Collections Research Center, I’d come across a number of references to the Dismal Swamp Land Company—founded by none other than George Washington—in the musty 200-year-old papers of a certain Fielding Lewis, proprietor of Weyanoke plantation on the James River. More on that later.) From Hampton, Brian and I drove down to Suffolk, on the south side of the James, and parked alongside three other cars at the Washington Ditch entrance to the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge.

The perfect fall weather—cool, still, with a bluebird sky—went a long way toward masking the treacherous nature of the swamp, which at one point covered over a million acres in this corner of Virginia and North Carolina. Still, as we strolled along the double track to Lake Drummond, a nine-mile hike in and out, we tried to invoke the ancestors: How would they have read the landscape, the channels and pools, the hummocks and scrims of scum, the large piles of seed-laden dung? On less benevolent days, how did they stay warm and dry? How did they eat? As the sun dropped in the sky and the woods around us became an impenetrable tangle of shadows, we quickened our step, arriving gratefully at the car, where we cranked up the heat as soon as we got in. Yes, it was in the 50s. Goes without saying that the ancestors were a hell of a lot tougher than we.

—Erin Hollaway Palmer, October 22, 2013

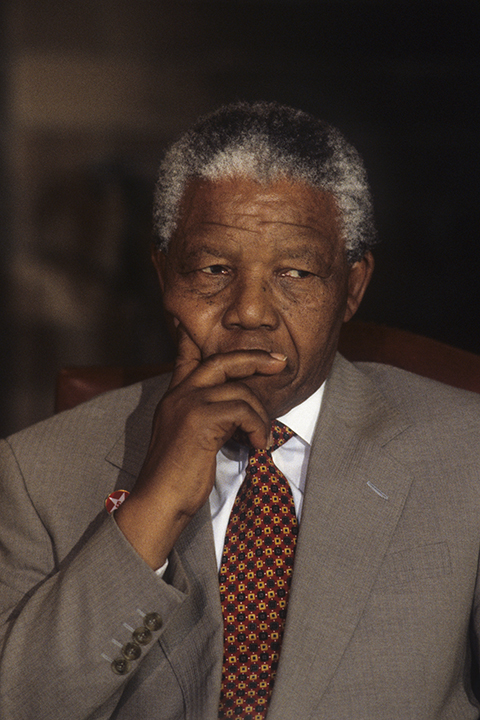

From the BXP photo archive: Mandela, July 1993

Nelson Mandela, then head of the African National Congress, came to Washington in July 1993. His visit coincided with that of then-South African president F.W. de Klerk. Later that year, they shared the Nobel Peace Prize, even as they were competing and contending in the runup to the first free election in the nation. This was a photo opp that my editors dispatched me to, a bit of Washington political theater. Mandela was not—could not—be defined by the cramped nature of the event. In fact, I can’t recall what the event was. There were prominent African American folks, mostly men in suits, on the dais with him, as I recall… but we were there for him.

From the BXP photo archives: Harlem, 2004; Taiwan, 1987

Development and Finishing Institute students learn dining etiquette at the Plaza Hotel, New York City, 2004

Rose Murdock started Harlem’s Development and Finishing Institute in 2002 to teach African American girls and Latinas (and later boys) etiquette and comportment. Bourgeois? Bien sûr! But Ms. Rose had no time or patience to indulge in debate. Her philosophy: Girls of color need every arrow in their quiver to succeed professionally and financially, from working a salad fork to speaking on the phone with a college recruiter or potential employer. Period. I respected that, though I did find the focus on the salad-fork side of things a bit much. Of course, Emily Post would have cringed watching me tuck into lunch.

The school is still up and running.

As I did years later in China—and everywhere else I have visited—I strayed from the main streets to learn and photograph. The boy had been tossing a rubber ball in the air but stopped when I approached. He faced me and posed. I made an exposure. I waved. He waved, and scooted off.

My ability to walk backward and speak passable Mandarin landed me a job as a legal proofreader in Taiwan, fresh our of college, in 1986. I had spent the summer of my junior year giving campus tours. My only takers on one dreary day in Providence, RI, were a family of three. Dad was a senior partner in a Taipei law firm; I was graduating with a degree in East Asian Studies. We chatted. He gave me his business card, told me to get in touch. I began pushing a pencil for him just a few months later.

The job entailed sitting in a cubicle at the back of the sprawling offices of Lee & Li Attorneys at Law, Monday through Friday and half of Saturday. My neighbor there was an elderly and flatulent translator.

I knew little of international law—Lee & Li’s core practice—and during the first couple of months managed to excise perfectly fine legalese from documents written by L&L’s U.S.-educated Taiwanese lawyers.

I had time on my hands, but I was duct taped to my admittedly comfortable chair. My workload had lightened after they hired another American proofreader. Plus, most of L&L’s attorneys spoke English fluently, so I wasn’t able to work on my Mandarin very much. I got quite good at the NY Times crossword puzzle in the International Herald Tribune. I also managed to work my way through an armload of novels. (Web surfing was far in the future.) And I lived for lunchtime at the cafeteria in the basement of the Formosa Plastics Building, L&L ‘s headquarters. Every day the steam table sagged under trays of scrambled eggs and tomatoes, various seaweeds, chicken and pork chunks, crunchy stir-fried veggies.

I had committed to a two-year term, but I had realized I was not lawyer material. I left after six months for the grand tour of Asia I had mapped out between puzzling and reading—China, Mongolia, the Soviet Far East, and beyond—only to get laid low by giardia in Nepal. That’s another story.

Virginia Wrap, Feb. 5, 2013

I’ve spent the last two-plus weeks in Virginia researching and interviewing for Make the Ground Talk, the documentary I’m making with Erin. We did the Richmond-Petersburg leg of the trip together, and she was here for a chunk of the current phase, Hampton-Williamsburg.

We’ve been hosted by my cousins Leon and Lois, and Joyce and Lankford Blair at the Magnolia House Inn. We have two homes away from home in Hampton.

We spent one Saturday at an oral history collection seminar at the College of William & Mary for the Lemon Project, an initiative undertaken by the school to unearth its unacknowledged roots in slavery. Brown University’s Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, spearheaded by former university president Ruth Simmons, provided a model for Lemon. (For history heads, the Committee’s final report is here.)

We must have done something right, because we’ve been invited to present our work at a Lemon Project symposium next month.

We’ve broadened—and deepened—the scope of the doc to include other African American towns, villages, and settlements that were uprooted in Virginia’s Tidewater, not just my great-grandfather and the vanished community of Magruder, where he lived. Turns out that many African American communities were wiped off the map to make way for a variety of installations and activities, and there are plenty of people interested in talking about them, including former residents and their descendants.

We’ve gathered a lot of material on this trip—documents, photos, audio and video interviews, broll—and plan to weave it into a new trailer during the coming weeks. We’ll shout when we have something to show.

BP

A Tree Grows in Hampton

We spent much of our last day in Virginia under the Emancipation Oak on the Hampton University campus. The weather was borderline miserable—wet, cold, gray—but it was the right place to be. It was also the right time to be there: 150 years from the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law.

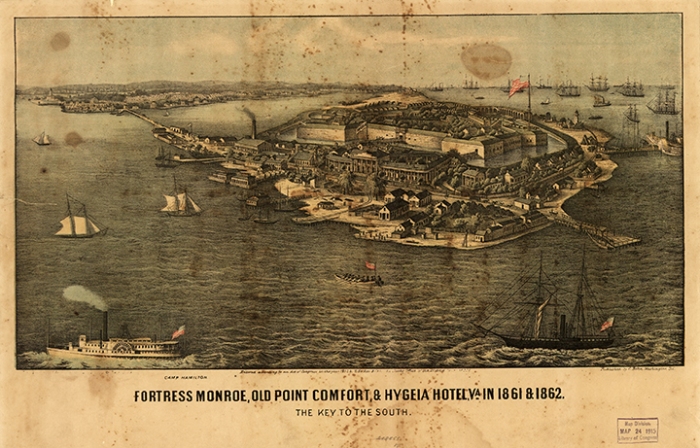

People gathered beneath this tree in January 1863 to hear the Proclamation read for the first time in the South. Among the listeners were men and women who had escaped from bondage and sought freedom behind Union Army lines, in places like Hampton’s Ft. Monroe, a Union stronghold in secessionist Virginia. By the end of the Civil War, tens of thousands of African Americans had fled to the safety of the fort and its environs.

Long before the Proclamation, in May 1861, Union General Benjamin Butler had refused to return the escaped men and women to slaveholders. He shrewdly claimed these people as “contraband of war.” Wartime law allowed Butler to seize the “property” of those rebelling against the United States, and that’s precisely what Confederates considered their slaves to be.

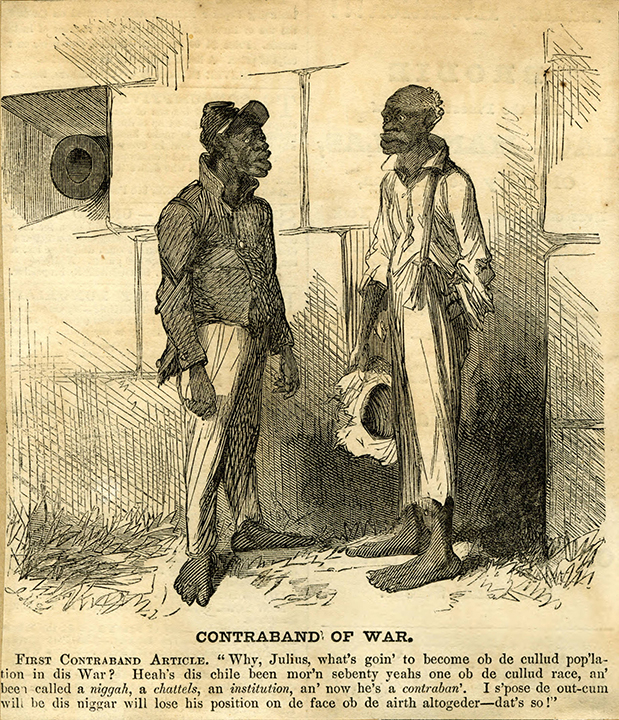

“Cumberland Landing, Va. Group of ‘contrabands’ at Foller’s house,” May 14, 1862, Photo by James F. Gibson, from Library of Congress

While the strength and dignity of self-liberated black folks is made plain by photos such as the one above, it’s clear from cartoons that even “enlightened” journalists clung to patronizing and racist stereotypes—though you gotta love the bare-chested brother blowing a raspberry at Rhett Butler (no relation to Benjamin).

Those gathered beneath the Oak had freed themselves, but they’d only stay free if the Union won the war. Historian Eric Foner reminds us in his op-ed in the New Year’s day issue of the New York Times that the Proclamation “could not even be enforced in most of the areas where it applied, which were under Confederate control.” But the document signaled Abraham Lincoln’s commitment to eradicating slavery and was a giant step toward the 13th Amendment, ratified at the end of 1865.

People started calling Ft. Monroe “Freedom’s Fortress,” and waves of so-called “contrabands” converged, and then dispersed across the area. They founded several communities radiating from Hampton; some, like the one that grew around the fort, were dubbed “Slabtown” for the ersatz materials freedmen used to build their shelters. More than a few of my ancestors undoubtedly settled in these encampments, which grew into towns. We visited the site of Yorktown’s Slabtown on our trip.

On our drive home north on Route 13, we passed through New Church, Virginia, on the border with Maryland. It’s not the first time we’ve seen this store, but each time the glowing sign reminds us of the durability and insidiousness of the Rebel myth.