Posts Tagged ‘scenic’

Virginia Wrap, Feb. 5, 2013

I’ve spent the last two-plus weeks in Virginia researching and interviewing for Make the Ground Talk, the documentary I’m making with Erin. We did the Richmond-Petersburg leg of the trip together, and she was here for a chunk of the current phase, Hampton-Williamsburg.

We’ve been hosted by my cousins Leon and Lois, and Joyce and Lankford Blair at the Magnolia House Inn. We have two homes away from home in Hampton.

We spent one Saturday at an oral history collection seminar at the College of William & Mary for the Lemon Project, an initiative undertaken by the school to unearth its unacknowledged roots in slavery. Brown University’s Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, spearheaded by former university president Ruth Simmons, provided a model for Lemon. (For history heads, the Committee’s final report is here.)

We must have done something right, because we’ve been invited to present our work at a Lemon Project symposium next month.

We’ve broadened—and deepened—the scope of the doc to include other African American towns, villages, and settlements that were uprooted in Virginia’s Tidewater, not just my great-grandfather and the vanished community of Magruder, where he lived. Turns out that many African American communities were wiped off the map to make way for a variety of installations and activities, and there are plenty of people interested in talking about them, including former residents and their descendants.

We’ve gathered a lot of material on this trip—documents, photos, audio and video interviews, broll—and plan to weave it into a new trailer during the coming weeks. We’ll shout when we have something to show.

BP

A Tree Grows in Hampton

We spent much of our last day in Virginia under the Emancipation Oak on the Hampton University campus. The weather was borderline miserable—wet, cold, gray—but it was the right place to be. It was also the right time to be there: 150 years from the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law.

People gathered beneath this tree in January 1863 to hear the Proclamation read for the first time in the South. Among the listeners were men and women who had escaped from bondage and sought freedom behind Union Army lines, in places like Hampton’s Ft. Monroe, a Union stronghold in secessionist Virginia. By the end of the Civil War, tens of thousands of African Americans had fled to the safety of the fort and its environs.

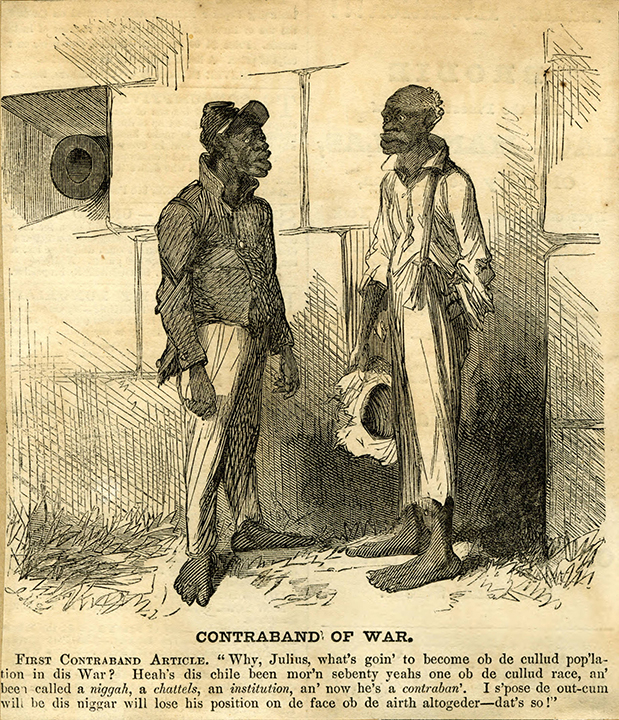

Long before the Proclamation, in May 1861, Union General Benjamin Butler had refused to return the escaped men and women to slaveholders. He shrewdly claimed these people as “contraband of war.” Wartime law allowed Butler to seize the “property” of those rebelling against the United States, and that’s precisely what Confederates considered their slaves to be.

“Cumberland Landing, Va. Group of ‘contrabands’ at Foller’s house,” May 14, 1862, Photo by James F. Gibson, from Library of Congress

While the strength and dignity of self-liberated black folks is made plain by photos such as the one above, it’s clear from cartoons that even “enlightened” journalists clung to patronizing and racist stereotypes—though you gotta love the bare-chested brother blowing a raspberry at Rhett Butler (no relation to Benjamin).

Those gathered beneath the Oak had freed themselves, but they’d only stay free if the Union won the war. Historian Eric Foner reminds us in his op-ed in the New Year’s day issue of the New York Times that the Proclamation “could not even be enforced in most of the areas where it applied, which were under Confederate control.” But the document signaled Abraham Lincoln’s commitment to eradicating slavery and was a giant step toward the 13th Amendment, ratified at the end of 1865.

People started calling Ft. Monroe “Freedom’s Fortress,” and waves of so-called “contrabands” converged, and then dispersed across the area. They founded several communities radiating from Hampton; some, like the one that grew around the fort, were dubbed “Slabtown” for the ersatz materials freedmen used to build their shelters. More than a few of my ancestors undoubtedly settled in these encampments, which grew into towns. We visited the site of Yorktown’s Slabtown on our trip.

On our drive home north on Route 13, we passed through New Church, Virginia, on the border with Maryland. It’s not the first time we’ve seen this store, but each time the glowing sign reminds us of the durability and insidiousness of the Rebel myth.